The making of

'Lightkeeper'

A Case Study In Designing for People

No matter the object of human centered design, the subject is always the same: humans.

When we set out to design good products and services we must start by forming an understanding of people’s goals and their motivations, their contradictions and their complexities.

In March of 2019, our team embarked on a journey of discovery: immersing ourselves in one of the most exhausting, emotional, and painful periods of people’s lives.

There are 2.8 million informal caregivers in Australia providing over $1billion worth of unpaid care every single week.

Informal caregiving is the unpaid backbone of the health and community services industry, yet there is surprisingly little support available for the millions of people who selflessly provide so much of their love, time, and attention each year. With an ageing population, declining fertility rates, and more women electing to stay in the workforce, it’s crucial that we greatly decrease the complexity, uncertainty, and administrative burden that accompanies the provision of informal care in Australia.

While almost every group of Australian's are represented by caregivers, our team immediately gravitated towards one...

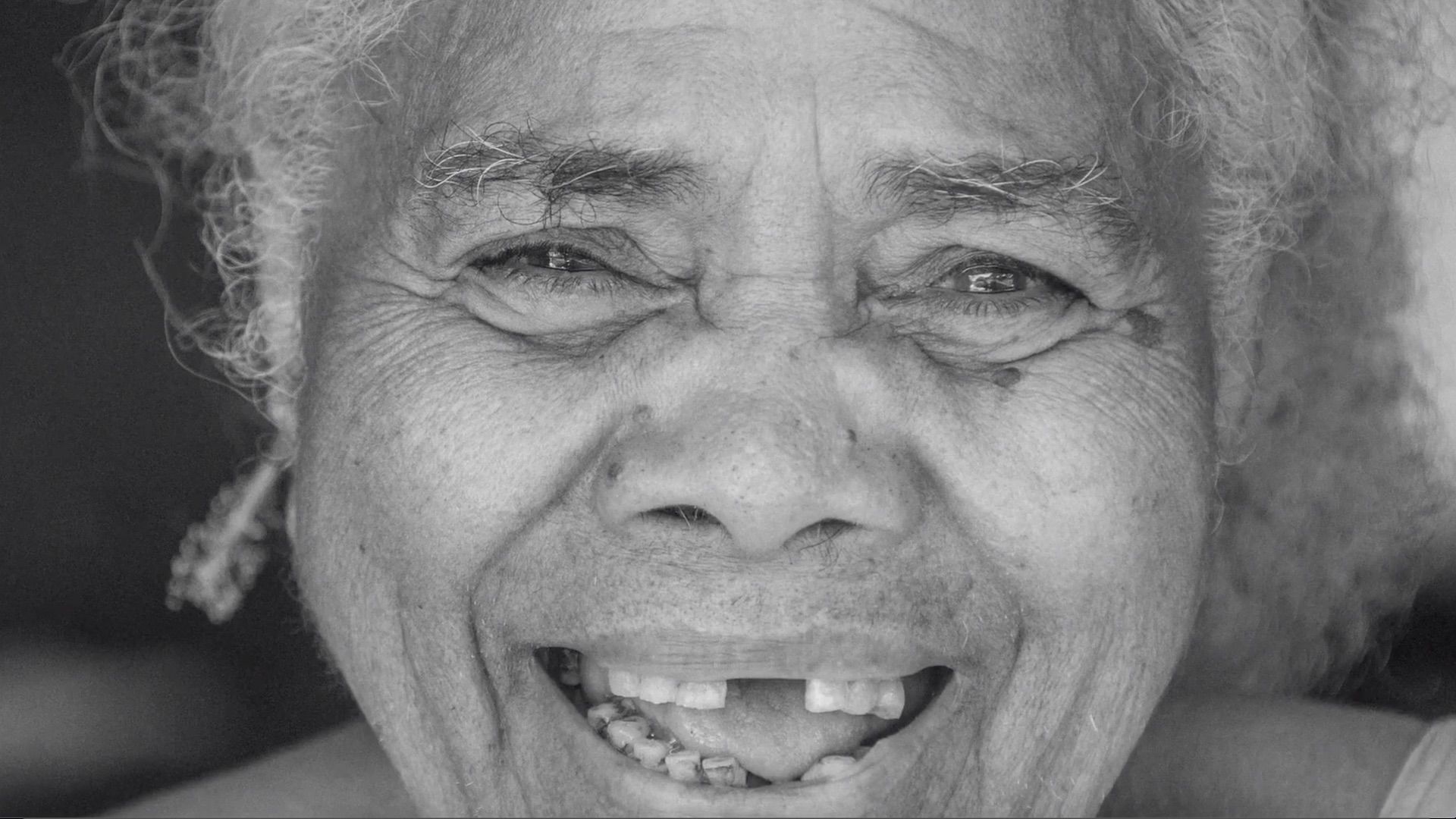

Kate

Kate represents a collection of people:

she is often the eldest sibling, is aged between 45 and 64, and is a ‘sandwich’ carer, providing care for both school-aged children and an ageing parent.

Our team urgently wanted to understand Kate, to immerse ourselves in her experiences and, more than anything, to do any little thing we could do to make her life easier.

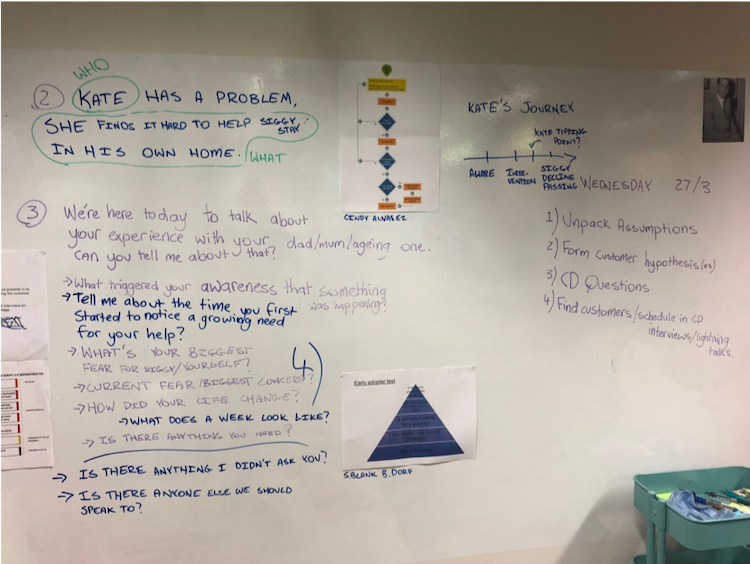

The easiest way to understand people’s emotions, stories, and ways of thinking about the world is through observation and conversation.

In an age of ‘big data’ it may come as a surprise that the rich insights required for innovation are readily found in small sample sizes. Lightkeeper’s complex narrative was built on the back of just 10 in-depth conversations.

As interviewers, our team’s role was to ask one or two very open-ended questions, and then to listen. We likened this experience to winding up a wind-up toy and then simply letting it go.

No true innovation is possible without learning to play the role of the unbiased listener; we need to ‘not know’ before and in order to ‘know’.

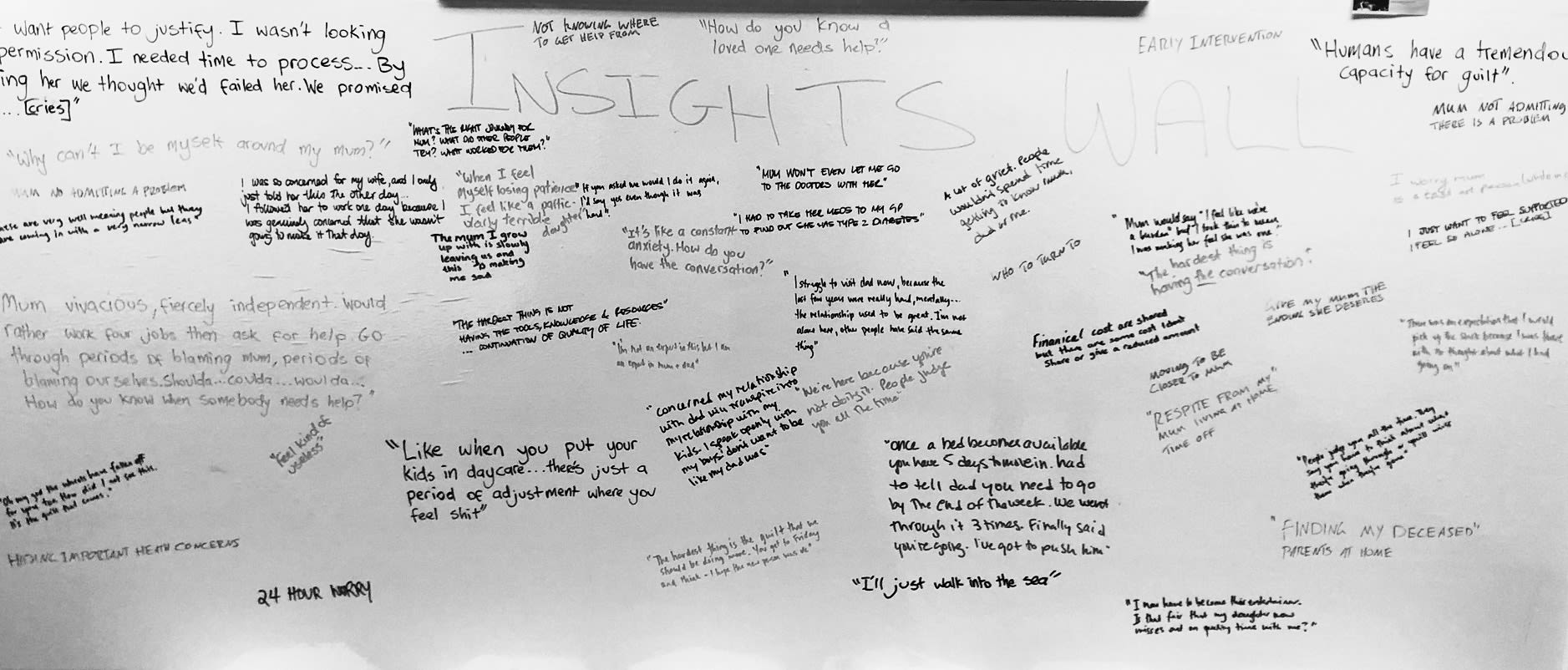

What we heard in our conversations were stories of courage,

of sadness, of bravery,

and of tremendous guilt; stories that embody the human experience.

We heard from Victoria that her mother wouldn’t engage with her in any kind of meaningful conversation about the end of her life, saying instead that when the time comes she’ll just “walk into the sea”.

We heard from Karen who lives in Brisbane and had to pack up her mum’s life in Canberra and get her into a nursing home within a week after her mum was found by police parked on the side of the road as she had forgotten where she was driving to.

We spoke to Greg whose family member passed away without a will. This has caused countless hours of pain and frustration for his family, sorting through loose ends with lawyers, banks and accountants.

From these 10 conversations we were able to build a picture of what life is like as a Kate, what the stresses and challenges are, how the journey unfolds, and how it reaches its heartbreaking conclusion. With a wealth of lived experience in our team complementing the notes from our conversations, this period of reflection and synthesis was heart rending.

There was a day, in mid-April, where 5 out of the 7 members of our team shed tears. We knew that we had stumbled into a period of people’s lives that was tense, emotional and typically endured in private. Shining a light on this period became a powerful and constant motivator.

Perhaps the most uncomfortable part of our entire Lightkeeper journey was deciding what our specific approach to helping Kates would be. We saw opportunities everywhere, and narrowing in on one felt jarring and almost cruel. We had hours of circular discussions and debates that got us nowhere. Eventually, our team agreed on the specific ‘problem’ that we wanted to address.

This problem can be described as follows:

'Despite intellectually understanding the ageing journey, for a variety of complex reasons Kates often find themselves in a situation where critical decisions regarding their parents have to be made quickly and under immense pressures. '

For a lot of us, knowing that our parents will one day pass away doesn’t mean that we prepare appropriately for this inevitability. In Australia, as in other Western cultures, we are very good at preparing for new life: we talk to our family and friends, we celebrate, we read, we learn the developmental stages, we nest.

At the other end of our time on this earth, things are very different. As a general rule we are devastatingly unprepared for death, even a death that has long been expected. We don’t have difficult conversations with our loved one’s until things reach a crisis point, we struggle to face mortality, we don’t understand the stages of the body and the mind’s deterioration, or all of the paper-work and administration that accompanies death (this last one may sound strange to those who’ve not yet experienced it).

Through providing Kate with an overview of the caring journey, allowing her to locate herself within this journey, and through giving her some timely advice on the practical things she could be doing, we believed we could enable her to make better decisions, earlier.

Death, like birth, follows a blueprint. While each is unique, there are signposts along the way, and a collective experience to draw from.

Armed with a shared understanding of both the ‘problem’ we wanted to address, and the way in which we wanted to address it, we entered the second stage of our journey, and begun to develop the product itself.

Too often when building products we leave out the entire empathise and define stages, failing to deeply understand the problem before jumping into designing a solution. The more mature an organisation is, the harder it can be to start with the clean slate required for truly innovative thinking. Effective human-centred-design in an established organisation is best understood as an exercise in forgetting. It’s a process of stripping away the layers of corporate history, internal politics, and current delivery models to return to the simplest and least asked question: what is it that people need?

It is estimated that over 90% of new products released by organisations fail. The largest reason for failure is not that a product isn’t compliant, or safe, or legally sound, or brand appropriate, or able to be delivered; the biggest reason for failure by far is that the new product doesn't address a market need. In other words, people don’t see the value of the product (or, perhaps even more likely, the product itself fails to provide real value).

Given the biggest hurdle for a product’s success is its market acceptance, it would stand to reason that we would test this towards the beginning of our product development processes. Unfortunately, this is typically the very last thing we test. Only when we’ve ensured that a product is fully compliant, safe, legally sound, brand appropriate, and able to be delivered do we test its market acceptance. This sequencing results in an enormous amount of waste, as the resources (time, money, and attention) required to get something through to market testing are immense, and crucially we have to do it all over again anyway if we’ve built the wrong thing.

We can try to address this problem by testing products early and often with unbiased, everyday people. This change in approach represents a trade off: on the one hand, testing a product's acceptance earlier greatly increases its chances of success, while on the other hand, it means putting something in front of people that hasn’t undergone the typical (expensive and time-consuming) checks, and therefore may not be as ‘polished’ as we are used to delivering.

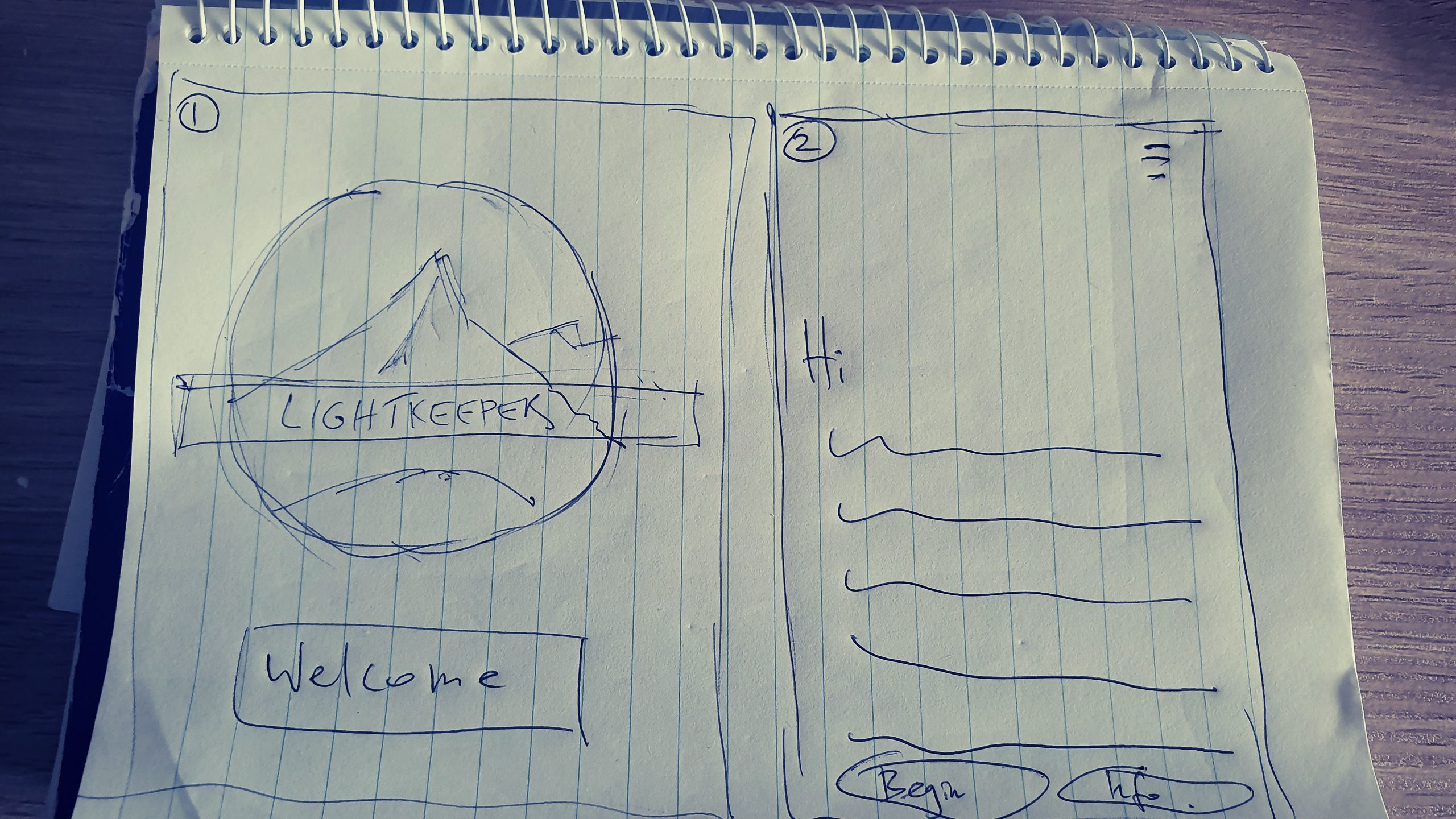

Lightkeeper has undergone 4 key stages of development to-date, and it is by no means ‘finished’ yet.

The design process is described as ‘nonlinear’ as you continue to learn about the ‘problem’ you are trying to solve by designing a solution. Action and creation need to accompany contemplation; you can only learn so much by thinking, at some point (probably earlier than most of us think) you need to begin doing (and, crucially, getting feedback). If you’re ‘doing’ correctly, you should be building enough to test your most critical assumptions, but no more.

The design process is described as ‘iterative’ as you repeat a simple loop of activities 3,4,5+ times. These activities are: use your beliefs about the problem you want to solve to design a solution, test this solution with real people, readjust your beliefs based on feedback, and repeat! Initially the solution will be very simple, quick to design, and inexpensive. Only when you begin to get more confident that what you’re building is valuable do you begin to expand considerable time and effort.

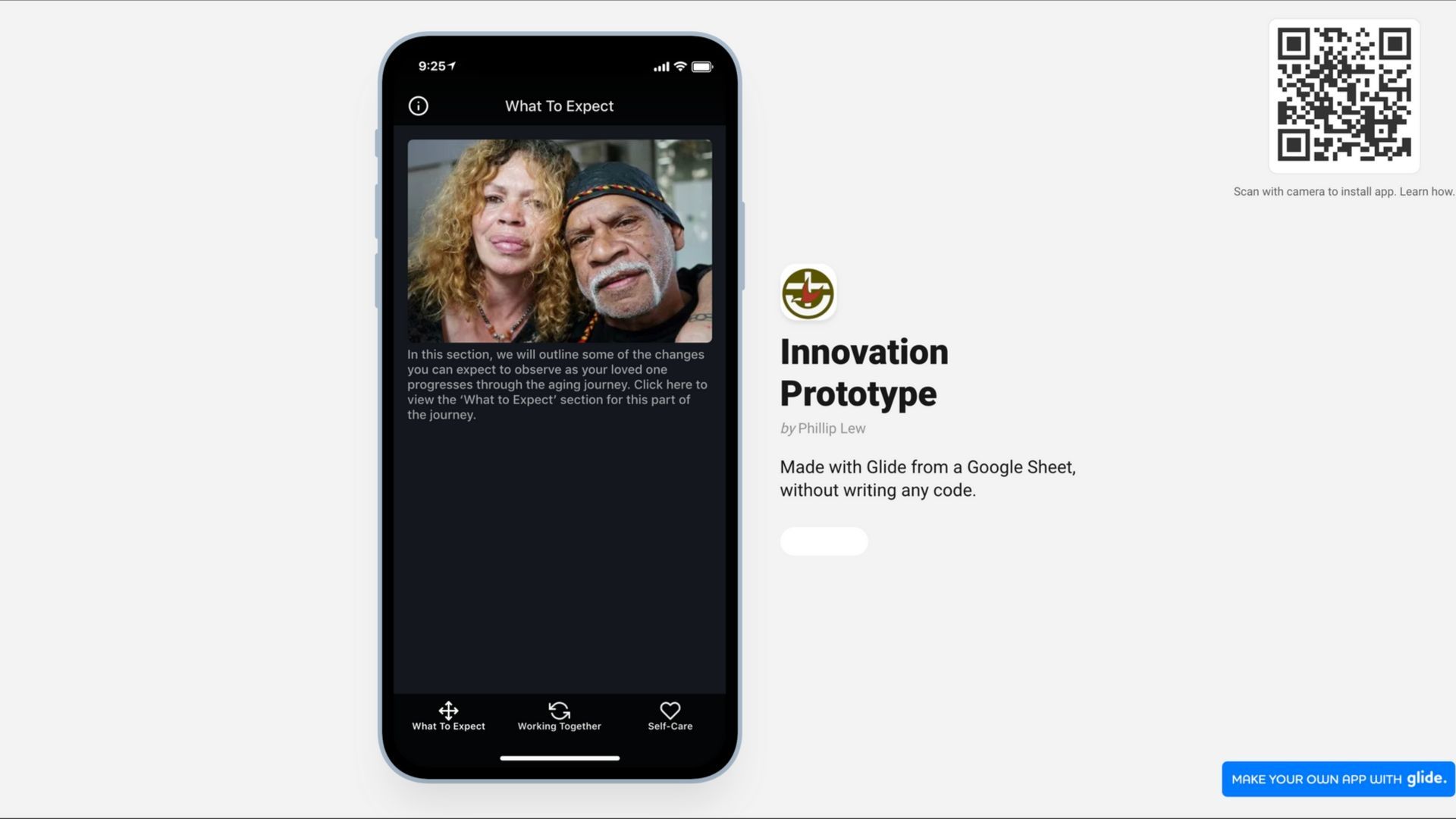

The first version of Lightkeeper was a very basic app designed without a line of code using a free tool called Glide that requires no technical expertise. This is so basic that one of our team members remarked on the discomfort she experienced when putting it in front of people.

In the early stages, prototypes can be better understood as conversation starters rather than as actual products. Responding to these early prototypes requires a bit of imagination, and some personality types will struggle to provide meaningful feedback (though I’m always surprised that most people have no issues at all).

Tool Cost: Free Time to Build: 1.5 hours Technical Difficulty: Very Low

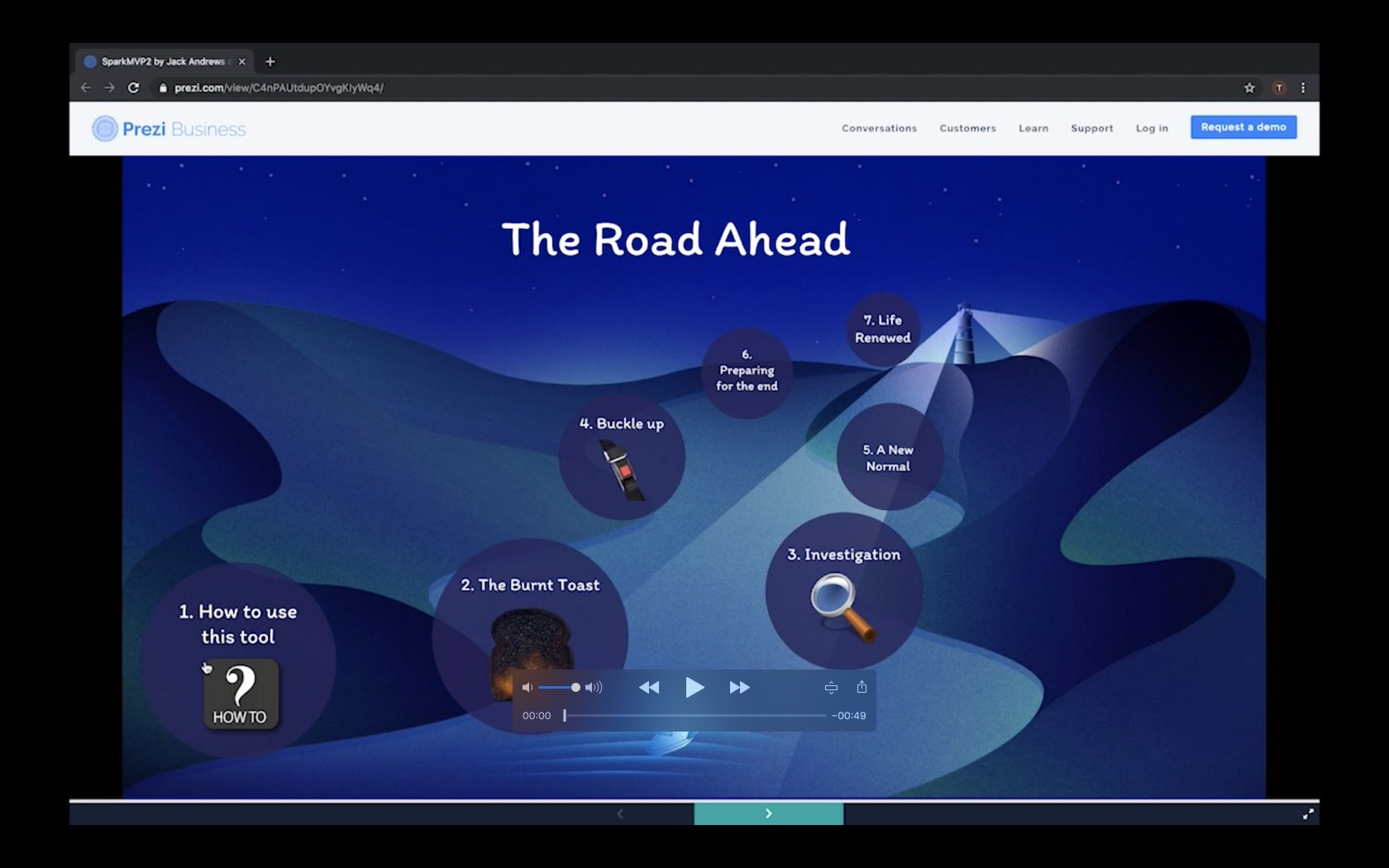

The second version was a powerpoint-like presentation, again built for free and without the need for any technical expertise using a tool called Prezi.

Once again, this was put in front of Kates and their feedback allowed us to understand what was valuable and what needed more thought.

The Prezi saw the emergence of a few key design elements that have been maintained through to the current version, like the segmentation of Kate’s journey by stages, and light and scaling a mountain as key metaphors.

Tool Cost: Free Time to Build: 3.5 hours. Technical Difficulty: Very Low

The third version was built in a UI prototyping tool called Figma, another that can be used comfortably for free. While Figma is more difficult to use than the first two, it was still something our team could handle internally without the need to engage specialist design or development expertise.

This prototype took longer to build and was far more sophisticated: creating an experience for our testers very hard to separate from using a real app.

Tool Cost: Free Time to Build: 30hours Technical Difficulty: Low

The fourth version of Lightkeeper (current at the time of writing) was built by Digital Purpose. After reaching the limit of our team’s capability, it was time to bring in some technical expertise.

Despite this phase being outsourced our focus was still on undertaking the bare minimum required to test our critical assumptions. It was essential to us that we found a partner who was able to work with us to land on these minimum requirements. We found such a partner in Digital Purpose.

Development Cost: less than $20k.

Time to Build: Elapsed time - 2 months.

Technical Difficulty: Outsourced.

Today’s version of Lightkeeper is still relatively basic, and we acknowledge that we have a long way to go. However we do believe it is developed enough for us to publicly release it, and that doing so should allow us to understand whether what we’ve created is of interest and of value to people.

While in some ways it feels premature for acknowledgements, getting things to this stage has required a lot of work, as well as the buy-in from a huge cast of players. I’d like to thank in particular:

UnitingCare for showing the bravery required to try something completely new. In particular: to Craig Barke, Cathy Thomas, Christian Patten, Tracey Mackie, Rob Ryan, Luke Garrett, and Matt Cuming. If we are to achieve different things we need to take different approaches, and your willingness to experiment has allowed us to get to where we are today.

Digital Purpose: Dan, Jo, Carmen and Martina - for your skill, responsiveness, patience, transparency, and partnership.

The Lean Startup team, who started with an analysis of megatrends in April of this year and have thrown work, sweat, and tears into getting Lightkeeper to this point. Thanks to Brooke Scutt, Adrian Juarez, Sharon Heenan, Che Turner, Jamie Ford, and Phil Lew. I hope this project will forever be special to you, as it will be to me.

To Jamie Ford, for saying yes to a time-intensive, highly-uncertain process with little chance of success, and for supporting both it and us from day one until today. UnitingCare owes you a debt of gratitude not yet fully understood.

To Phil Lew, for your immense talent, care, effort, focus, and attention. I know we have a long way to go, but I hope that you are as proud of your work as I am.

Finally, to the 30-strong cast of Kate’s who have helped us get to this point. Without your insight, experience, feedback, and unwavering support, Lightkeeper would not exist.

We are hugely excited to see where our journey with Kate takes us next, and to continue our work in building an organisation that is innovative, customer-focussed, and responsive to the needs of people.

To get involved you can check out the web-app here, or donate to keep Lightkeeper going here.

Thanks for reading,

Jack Andrews

LinkedIn